Caught in the ripples of a receding tide

MY FATHER’S EXPERIENCE AS A SOLDIER AT THE END OF THE BRITISH MANDATE IN PALESTINE IN 1946

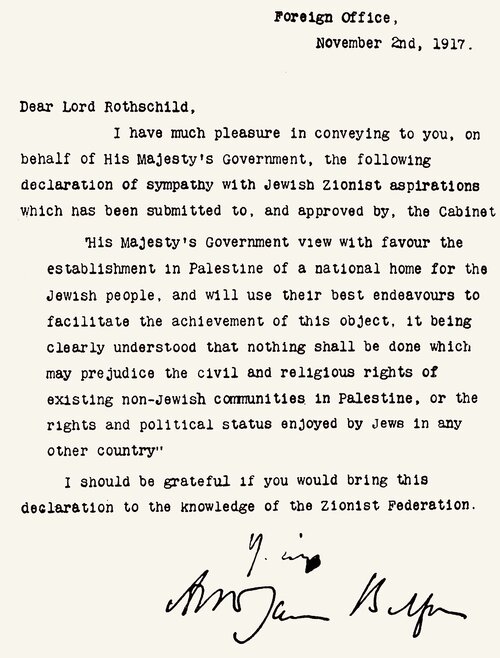

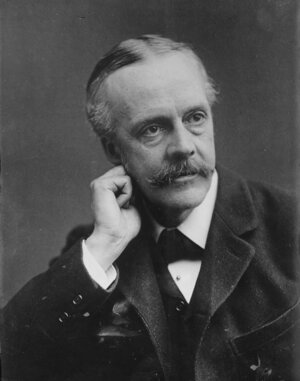

A hundred years ago, on 2nd November 1917, British foreign secretary Lord Arthur James Balfour wrote to Lord Walter Rothschild, considered at the time to be the leader of British Jews, to declare that the British government supported the establishment of a home for Jews in Palestine, then under the dominion of the Ottoman Empire.

The centenary of the Balfour Declaration has passed without the recognition it deserved. For the British, the Declaration led to their mandate in Palestine which lasted until, exhausted and bankrupt by the Second World War, they withdrew, leaving the Jews and Arabs to fight it out.

It was a complicated and messy episode in which Britain managed to incur the enmity of both the Arabs and Jews and leave behind a conflict which still is unsettled after a hundred years.

But we shouldn’t let it pass unconsidered. It is an object lesson in the law of unintended consequences. When Balfour penned his lofty note of 117 words to Lord Rothschild in 1917, declaring that the Jewish people should have a national home in Palestine, he unwittingly set in motion the events that would lead almost thirty years later to my father, a young British second lieutenant in the Royal Engineers, leading a boarding party onto the sloping decks of an ‘Illegal’ Jewish refugee ship in Haifa Harbour in order to detain and deport the passengers.

WHY DID LORD BALFOUR WRITE THIS DECLARATION?

Quite what motivated Balfour has been the subject of much historical debate. Some historians have painted him as a philo-Semite who simply wanted to right an ancient wrong and restore the Jews to their biblical lands after eighteen centuries of exile.

Others have painted him as a typical early twentieth century British anti-Semite of the John Buchan variety who believed that an international network of powerful Jews had such influence in Washington that they could prevail upon President Woodrow Wilson to speed up the deployment of American troops to the Western Front where the situation was looking decidedly grim for Britain and France as their Russian ally teetered on the brink of revolution.

A British version of this idea has the bankrupt British government bending over backwards to appease the Rothschild banking family, but this ignores the fact that of the two Jews in the British Cabinet, only one, Herbert Samuel was a keen proponent of the Declaration, while the other, Edwin Montagu, vehemently opposed it on the grounds that it would prejudice the position of Jews living in Britain who didn’t want to emigrate to a new ‘national home’ in Palestine.

Historians taking a longer view of British imperial policy see Balfour’s Declaration as a small element in a larger plan to establish a pro-British (and anti-French) enclave in the much disputed and strategically interesting area between the Mediterranean and Jordan. Historians focusing on the short-term and personal nature of events suggest that this was Balfour’s way of making a personal thank you to Chaim Weizmann, a leading Zionist who was also the chemistry professor at Manchester University responsible for discovering how to fabricate acetone an important and scarce element in munitions manufacture.

The least persuasive idea is that Balfour, imbued with a romantic religious zeal, was working in the tradition of English evangelical Protestants like Oliver Cromwell and General Gordon (the latter during his Jerusalem visit claimed he had discovered the real cave in which Joseph of Arimethea had entombed Jesus). It’s too hard to believe that a worldly, and on occasion cynical, statesman like Balfour believed that the Second Coming would be made possible by the restoration (and of course conversion to Christianity) of all the Jews in the world to the lands of Israel and Canaan.

WHAT WAS THE IMPACT OF THE BALFOUR DECLARATION?

This is an object lesson in another historical truism: what might seem to be a good idea to someone in power at one moment in time will profoundly shape the lives of ordinary people for generations.

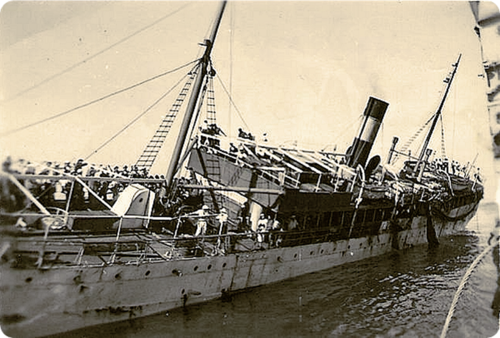

This is really a story about two such ordinary people, two twenty-year-olds. One is my father, John Davies, a Welsh Baptist called up to National Service in between Hitchin Grammar School and Oxford. The other, Solomon Veingold, is a Russian Jew from Hotin, Bessarabia, who had spent the previous five years homeless and stateless and was hoping to join the burgeoning Jewish community in Palestine. Their momentary encounter on the deck of the San Demetrio, a Jewish refugee ship in Haifa harbour on the morning of 8th November 1946, illuminates a forgotten moment in our imperial past and the contradictions inherent in the Balfour Declaration.

In 1946 British forces were still tasked with stemming the flow of ‘illegal’ Jewish immigration into Palestine. The British government adhered in public to the policy that Jewish immigration should not be at the expense of the Arab population of Palestine. In private, almost before the ink was dry on Balfour’s signature, many British politicians realized that the Declaration could never deliver a national home to the Jews without impinging on the national home for the Palestinian Arabs. My father, like many soldiers before and after him, had the unenviable task of implementing a failed policy long after the politicians who authored it had given up.

In a letter home on 6th November 1946 my father described the events of the previous day. The San Demetrio had been intercepted by HMS Providence in the eastern Mediterranean on the 1st November and was now being escorted into Haifa harbour. His job was to board the San Demetrio when it docked, detain everyone on board, and then escort them to another ship and sail with them to detention camps in Cyprus

His letter starts with a moan about being made to camp overnight at the docks and endure the flies. He marvels at the ingenuity of the men in his boarding party who had armed themselves with a ferocious array of homemade weapons – an iron bar with a cruel hook on the end and cudgels embedded with six-inch nails.

He describes in vivid detail the appalling conditions on board the overloaded ship. It was listing 18 degrees when it limped into port under the eyes of a Royal Navy destroyer, and below deck the floors were slippery with excrement and vomit. Some of the passengers were resigned to their arrest but others fought the British soldiers who were trying to force them down the gangway.

He describes one “huge wild woman … like an Old Testament prophetess” railing against them. He writes with outrage about how Jews spat at them and shouted “Nazis!”. He recorded all the evidence he saw of the American financing and organization of the refugee efforts left onboard the ship, discarded US rations boxes and equipment, and echoes a general British exasperation about having to play second fiddle to the US in the post-war world order.

Brought up a Baptist in a Nonconformist Welsh household and a regular attendee at the Tilehouse Baptist Church sunday school, my father’s knowledge of the geography of Palestine was rooted in the Bible. His other letters home were full of observations of ‘typically biblical’ scenes like village women drawing water from a communal well.

This letter is different. The tone at the start is breezy and he signs off with the usual requests to be remembered to various friends and relations and sends his hope that the Liberal candidate in the local by-election will do well (his grandparents on both sides were dyed-in-the-wool Gladstonian Liberals).

The middle part of the letter is much darker. He describes searching the black and fetid hold, his eyes stinging from the tear gas which still lingered below deck, to find anyone still hiding. Men dragging a woman down the gangway like a “sack of potatoes”. It leaves no illusions as to how repugnant he found the whole experience.

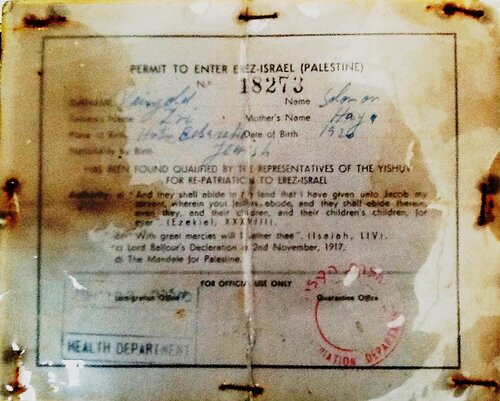

Before he died, he gave me a memento of this event in his life. As the ship was being cleared he saw a young man drop something on the deck – it was a fake passport made out to Solomon Veingold from Hotin in Bessarabia (now Moldova) who, like my father was born in 1926. In a mixture of English and Hebrew it promised the bearer, on the authority of the Old Testament prophets Ezekiel and Isiah, and Lord Balfour no less, the right of entry to Eretz (former) Israel.

We can only make an educated guess at Solomon’s back story. It’s almost certain that he was one of the majority of the Jewish community who abandoned Hotin and fled east with the retreating Soviet army in the summer of 1941 (because those who remained perished), and that he spent the war years somewhere in central or eastern Russia. After the war he became one of the millions of displaced people whose homes or even countries no longer existed and who moved across Europe in search of a better life.

Somehow by 1946 he had got himself to Marseilles which was a hub for the Zionist organisation which issued him with his ‘passport’. Their purpose was to help Jews reach Israel and they looked for ship owners and ship captains willing to take a human cargo to Palestine for the right price. The ships were usually reaching the end of their working life and the captain and small crew, who knew they would be arrested if caught, desperate for money. These ships were also used to smuggle men and weapons.

Nir Maor, director of the Clandestine Immigration and Navy Museum in Haifa, showed me his records on the San Demetrio. My father’s search party failed to discover four men sealed into a compartment behind the ship’s boiler who later escaped to join the nascent Jewish army (the Hagganah) readying itself for the civil war which would erupt when the British left. Unfortunately my father had died before I could point out this oversight on his part.

Solomon and the other refugees detained by my father were taken under guard to another ship in which he and his detachment sailed with them to Cyprus, which at that time was still a British dominion. The British government had no clear plan about what to do with the Jews they held in detention camps, so what usually happened also happened in this case, and the refugees were kept in Cyprus for 4-5 weeks before the British buckled under American pressure and quietly readmitted them to Palestine as legal immigrants with the proper authority.

Given that Solomon had lost his identity papers he could easily have disappeared from sight, but I’m almost certain that we do catch another glimpse of him on 11th December, 1946. A Nechama Weingold, born in ‘Hotin Romania’ and aged 22, is admitted into Palestine from Cyprus along with her spouse who is recorded as Shlomo Weingold. I think Solomon has hebraicised his name to Shlomo, Veingold has been rerecorded as Weingold, a common transliteration, and Hotin, Romania is the same place as Hotin, Bessarabia, although by 1946 both designations were wrong as Hotin was now firmly in the USSR.

Of the three societies most affected by the Balfour Declaration – British, Israeli and Palestinian – it is the latter where Balfour is best remembered, and not kindly. The British have forgotten him along with the thirty-year mandate in Palestine, and the Israelis understandably emphasize the role of Jewish determination rather than imperial largesse.

It’s the Palestinians who remember Balfour and his arrogance in choosing to give away rights to a land that the British had no claim on, without taking into account the views of the people who lived there.

The last time I walked through Nablus market and admitted I was British, the stall holder shouted: “ … and what about Balfour?”

Michael Davies taught history at Lancaster Royal Grammar School and now runs Parallel Histories.