Cromwell and Empire

At Parallel Histories we focus on ensuring that students discuss and debate the most controversial historical topics, including the role of the British Empire. Britain’s status as the capital of a much larger political entity is relevant to every aspect of its history. We have produced a new product on Oliver Cromwell, a man commonly studied in British schools but not particularly associated with Empire. Why not? The obvious answer is because the Empire was far from its peak. But the colonization of the Americas had started, while subduing Ireland – Britain’s oldest colony – was a major aspect of Cromwell’s rule.

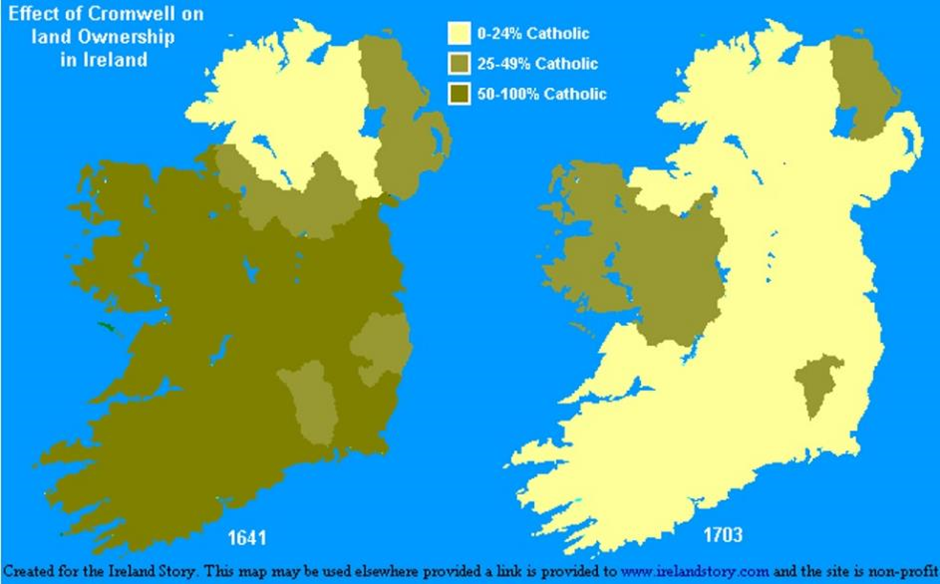

Our dual narrative methodology brings Cromwell’s role in developing the British Empire to the forefront. It gives the narrative of the colonized equal weight to that of the English perspective on Cromwell. Ireland rarely factors into modern discussions of Empire, and yet it was the testing ground for colonial policies that were later implemented much further afield by the British state. See for example, Cromwell’s use of plantations in Ireland:

The removal of land from Irish ownership and its placement into the hands of English settlers, whether it was justified or not, is certainly imperial in nature. Some historians have even called it ethnic cleansing. Transforming the structure of society by transferring huge

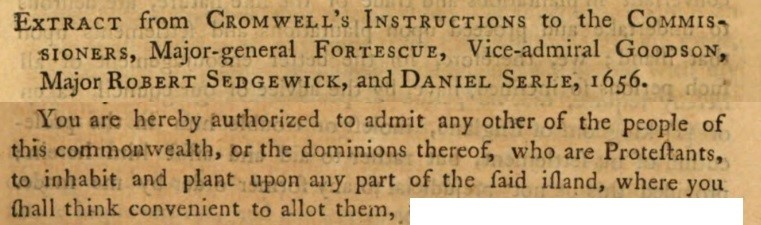

tracts of land into the hands of loyal settlers was not only used in Ireland. Cromwell himself used this approach to colonisation when he conquered Jamaica:

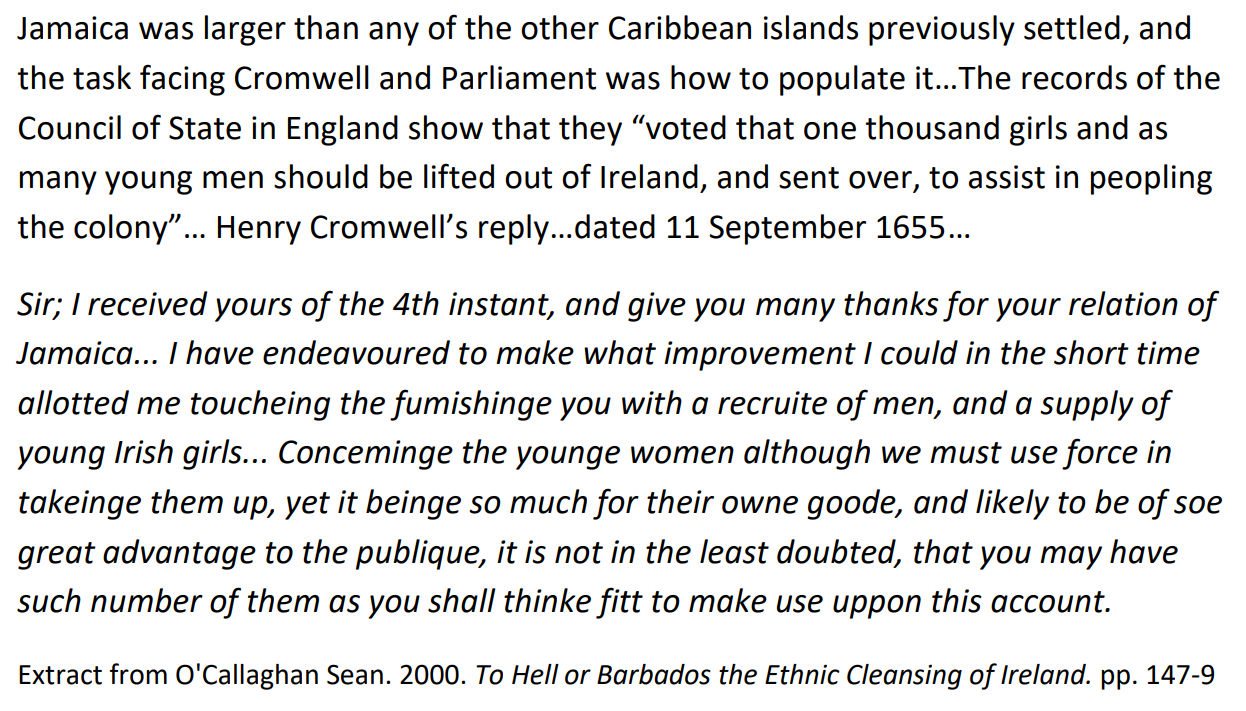

There is even a direct connection between the colonies of Ireland and Jamaica, as Irish people were often sent to work as indentured servants in the Caribbean:

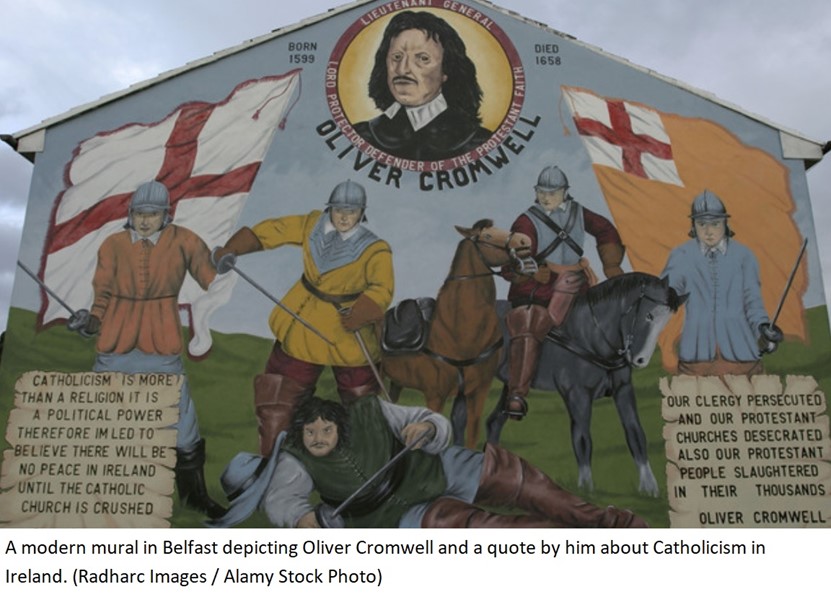

Similarly, the British imperial policy of ‘divide and rule’, later used in India to foment unrest between Hindus and Muslims, was first tried in Ireland. Cromwell hardened the divisions between Protestants and Catholics in Ireland with his penal laws, which banned Catholics from becoming MPs and living in towns. This division did predate Cromwell, but he pushed it further, as would the English rulers who followed him. The legacy of this religious division in Irish society, and Cromwell’s role in it, is still clearly visible in the Protestant, Unionist community in Northern Ireland:

Focussing on the imperial aspects of Cromwell’s rule, forces students to examine him through debates that are rarely had in the classroom. In the UK, Cromwell’s legacy is frequently defined by the tension between his push for parliamentary government versus his status as ‘king in all but name’ as Lord Protector. While this is an important and substantial debate, it takes on a different light when we consider that Cromwell conducted policies in Ireland branded by historians as ethnic cleansing. Whether the troops burning your house and forcing you off the land are under the command of a general who was a loyal servant of parliament or sought monarchical powers for himself was an irrelevant question for the inhabitants of Wexford, Waterford, Drogheda and Clonmel. However, for Unionists in Northern Ireland, Cromwell represents an English ruler who was willing to protect their endangered minority population from the hostile, Irish Catholic majority. Parallel Histories’ Cromwell programme gives you the resources to explore and debate his role in the British Empire in the classroom.