Making sources fun, not formulaic

One of the most important but also hardest challenge facing every history teacher is introducing their students to source evidence and how to evaluate it. It’s not always something that students immediately or intuitively grasp, and teachers have tried numerous different ways of scaffolding the learning process. Acronyms like PEE (Point Example and Explanation) abound as teachers attempt to codify and simplify what they are asking students to do. However, the danger is that students get stuck on the mnemonic and find it hard to move beyond a formulaic approach which they apply regardless of the historical context of the source they are examining. An example of that formulaic approach could be “this source is useful because it was created at the time”, or the contradictory, ‘this source is useful because it was written after the event and will have hindsight’’ . This article has a few ideas I have generated over my teaching experience which I hope will be helpful to teachers who are trying to get their students to think like young historians.

One of the most important but also hardest challenge facing every history teacher is introducing their students to source evidence and how to evaluate it. It’s not always something that students immediately or intuitively grasp, and teachers have tried numerous different ways of scaffolding the learning process. Acronyms like PEE (Point Example and Explanation) abound as teachers attempt to codify and simplify what they are asking students to do. However, the danger is that students get stuck on the mnemonic and find it hard to move beyond a formulaic approach which they apply regardless of the historical context of the source they are examining. An example of that formulaic approach could be “this source is useful because it was created at the time”, or the contradictory, ‘this source is useful because it was written after the event and will have hindsight’’ . This article has a few ideas I have generated over my teaching experience which I hope will be helpful to teachers who are trying to get their students to think like young historians.

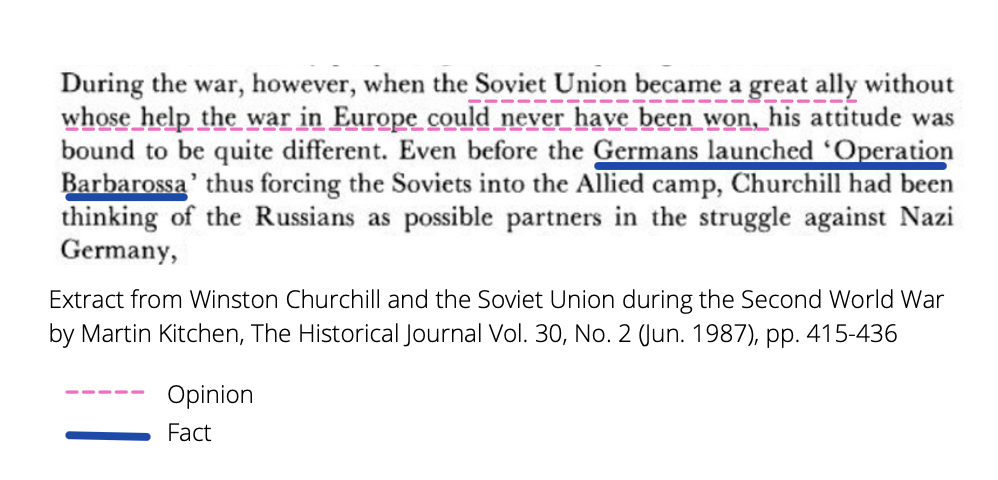

Fact or Opinion?

The first building block is to check that your students understand the difference between fact and opinion. The approach I used was to ask students to highlight words and phrases that describe situations or people and underline statistics, dates to show the facts.

This task can be a starter activity before you delve into evaluating sources.

o Hitler died in 1945

o Stalin was a bad leader

o Henry VIII was a 16th century English king

o The Cold War was important

o WWI started in 1914

o WWI was caused by the assassination of Archduke Franz-Ferdinand in Sarajevo

I would then explore a source together as a class. Ask a student to read a source aloud, promoting oracy in the classroom. Then lead a discussion on what the source is telling you as historians. Following this discussion, encourage students to explore the source further, by looking for facts and opinions, demonstrated in the source here:

By the way, this source is from our Historical Figures Series, Does Churchill Deserve the Status as the Greatest Briton? Throughout this article, we will explore different approaches with sources from this series

Knowledge or Evidence?

The second building block is to help students understand the difference between knowledge and evidence. This is harder for many students; a common error when younger students first come across source evidence is that they use primary sources as knowledge rather than a piece of evidence from the past that they need to interrogate through asking questions. Therefore, before deconstructing sources, students need to know the difference between knowledge and evidence

The approaches I used here tended to vary according to the class, but one constant feature was to insist that they approach every source with caution and a questioning mindset.

Through adapting a ‘questioning’ approach, students already are building their lines of enquiry from asking simple questions such as “what can I comprehend from this source” to “from my own knowledge, what was happening at the time and in what ways could this limit its reliability?”

When analysing sources, it is advantageous that students ask themselves these questions:

· What can I learn from this source about the past?

· How useful is this source in my enquiry?

· Is this a reliable source about the events it portrays?

· How relevant is this source for my enquiry?

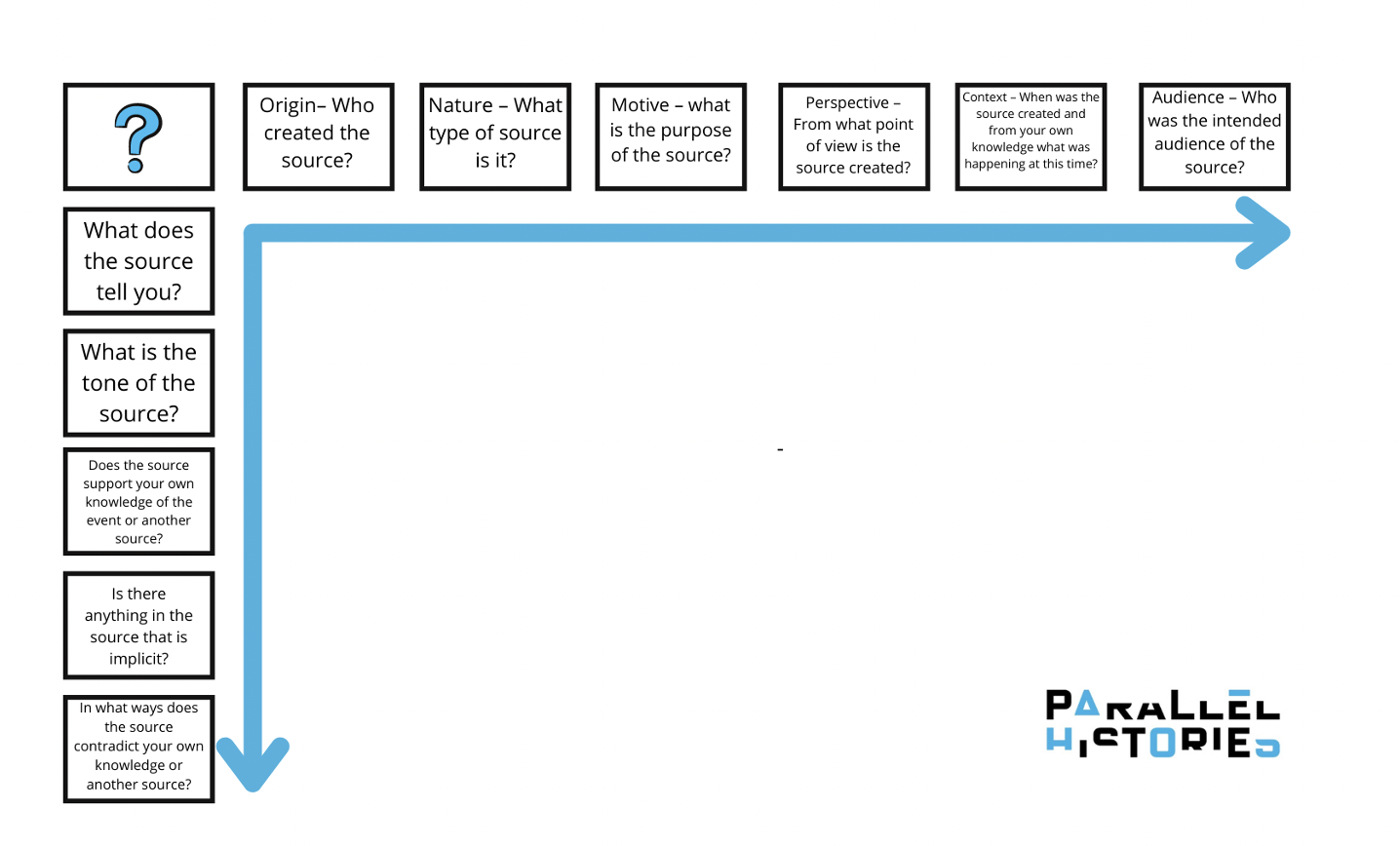

Step 1: Annotating the features of the source:

At this stage, it is good practice for students to identify different features of the source before adding depth to their enquiries. These questions could be useful when encouraging students to continuously annotate their sources before they formulate a response.

Questioning the content

– What does the source explicitly tell you?

– Is there anything in the source that is implicit?

– Does the source support your own knowledge of the event or another source?

– In what ways does the source contradict your own knowledge or another source?

Questioning the author

– Origin– Who created the source?

– Nature – What type of source is it?

– Motive – what is the purpose of the source?

– Perspective – From what point of view is the source created?

– Context – When was the source created and from your own knowledge what was happening at this time?

– Audience – Who was the intended audience of the source?

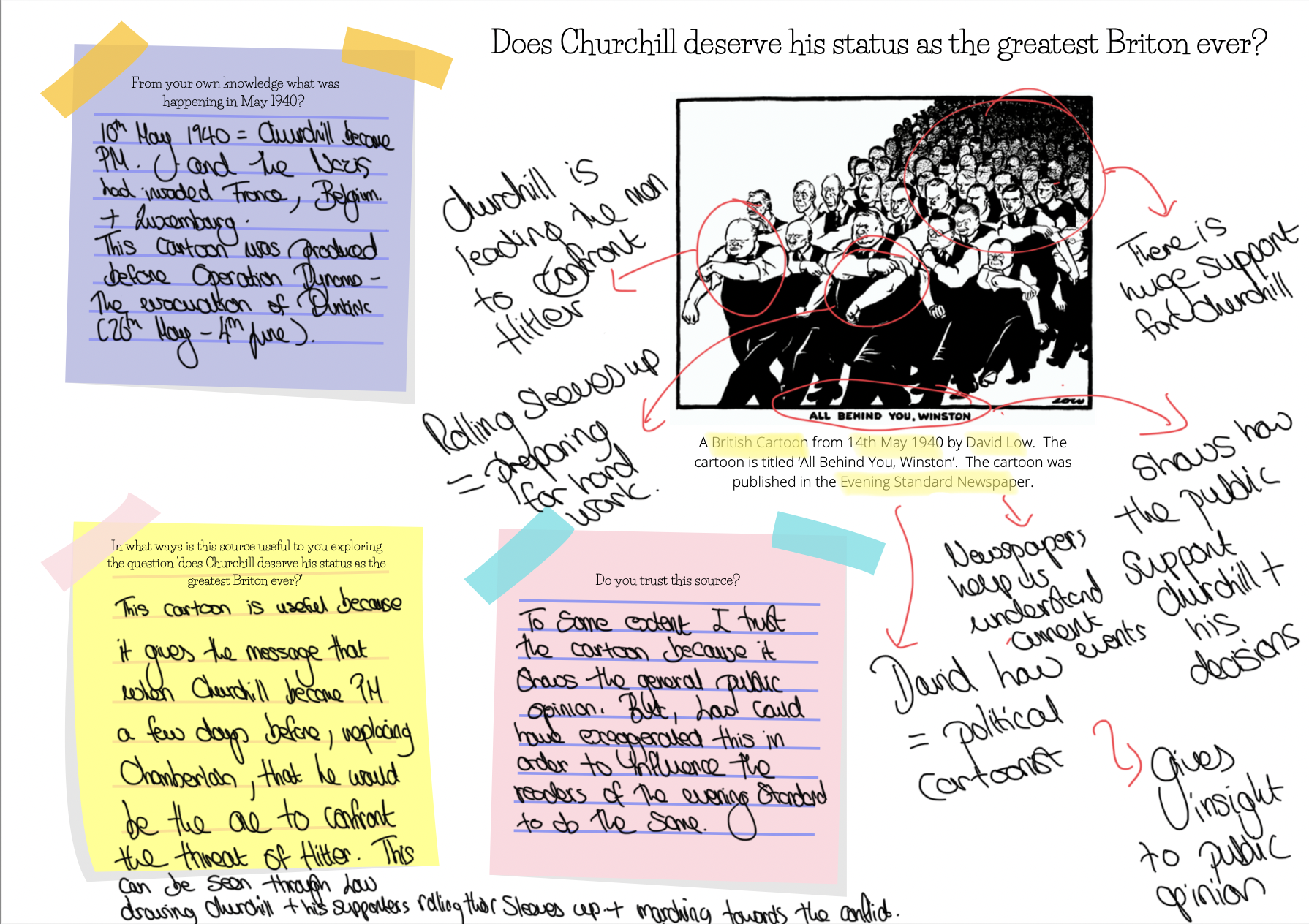

ASKING SPECIFIC QUESTIONS HELPS STUDENTS FOCUS ON SPECIFIC FEATURES OF THE SOURCE. THIS CAN BE BROKEN DOWN FURTHER FOR DIFFERENTIATION BY ASKING MORE DIRECTED QUESTIONS ABOUT THE CARTOON. IT IS A GOOD IDEA BEFORE EVALUATING A SOURCE TO ASK STUDENTS TO WRITE DOWN FACTS ABOUT WHAT THEY KNOW HAPPENED DURING THE TIME. IN THIS CASE, MAY 1940.

Step 2: Adding depth to your analysis

The next step is adding depth to your analysis. You could encourage students to make comments about the usefulness and reliability of the source.

Assessing the reliability of sources and how useful they are to us as historians

· Reliability is whether you trust what you’ve read, see or from the author that produced the source.

· Utility is what features is useful to a historian studying a particular period

o Highlight phrases that you question

o How much can we trust what it tells us?

o Has anything been exaggerated?

o Why has it been produced?

o Does it match your knowledge?

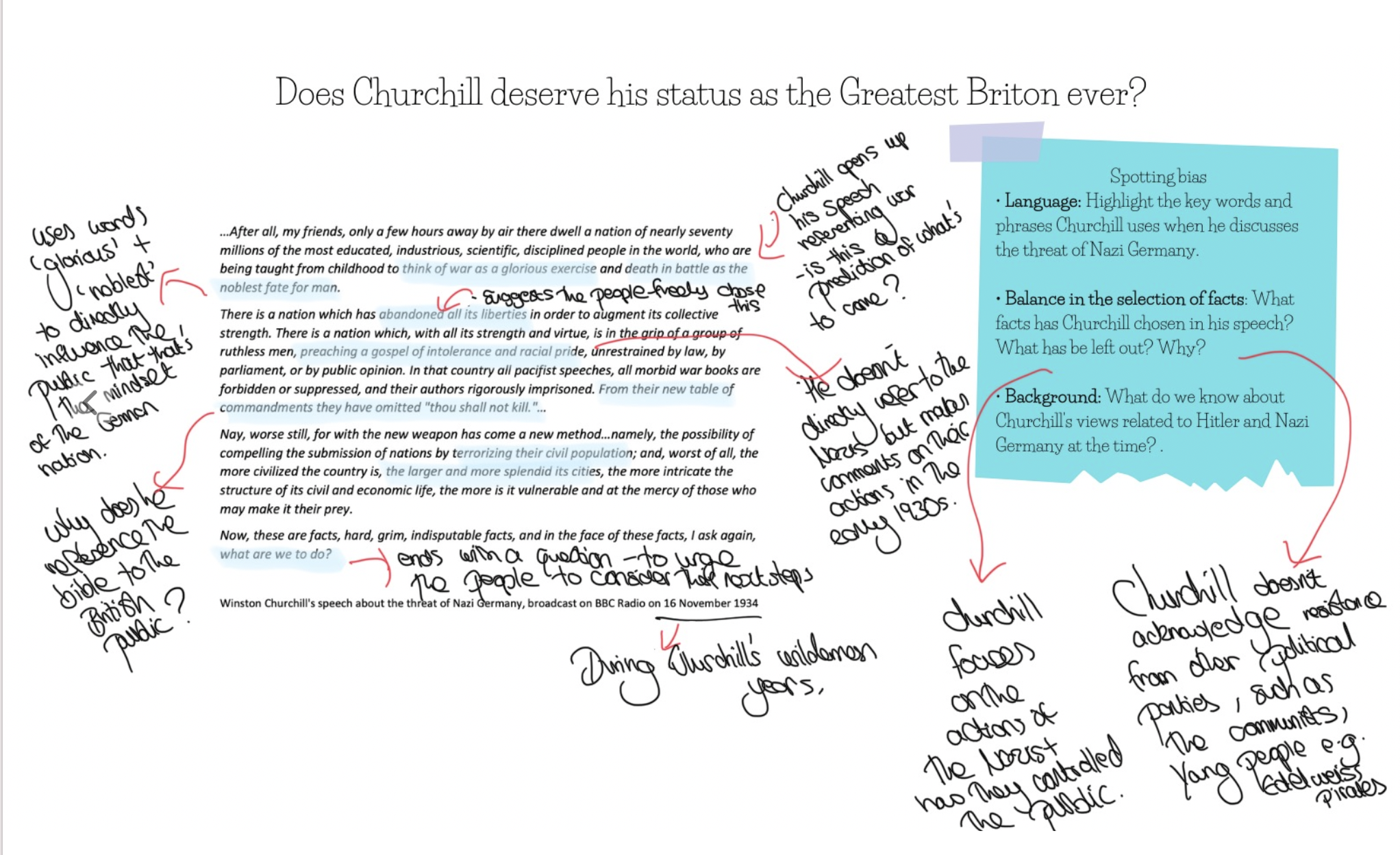

How to spot bias

· Language: the use of certain words can often reveal a person’s bias. For example, when talking about a strike someone might call the workers “bone idle” or “wicked individuals”.

· Balance in the selection of facts: if you have a basic knowledge of the topic being studied, you can look for facts which have been left out. By leaving out details and highlighting others, a source can influence the reader in a particular direction.

· Background: we all have different views and what we see is influenced by them. Knowledge of the views behind the source will help in the identification of bias.

THIS ACTIVITY GIVES 3 THINGS STUDENTS NEED TO FOCUS ON WHEN EXPLORING THE SOURCE: LANGUAGE, BALANCE IN THE SELECTION OF FACTS AND THE BACKGROUND OF THE AUTHOR. THIS ACTIVITY CAN BE COMPLETED AS AN INDEPENDENT TASK OR AS A WHOLE CLASS, EXPLORING ONE KEY FOCUS AT A TIME.

How do I build these skills when preparing students for a digital debate?

Once you have completed steps one and two of Parallel Histories 3-step teaching methodology, students will have engaged in many arguments about Churchill, one being:

Churchill observed the threat Hitler posed in the early 1930s.

Through an extended writing activity, you could ask students to support their argument with knowledge and evidence from the source. Here, you can ask students to explore the sources and choose one that supports their argument. Let’s look at this example you could adapt when encouraging students to write their speeches:

For example, Churchill’s speech, made in November 1934 could be in response to Hitler having complete control in Germany in 1934, as Churchill directly states to his audience, “there is a nation which has abandoned all its liberties in order to augment its collective strength”. Hitler controlled the government, trade unions and removed his opposition through his use of the Enabling Act, 1933. Churchill’s intended audience could be the British public, as Churchill was isolated by the Conservative Party, and he used the 1930s to voice his attitudes towards Germany and he could be more honest with his audience.

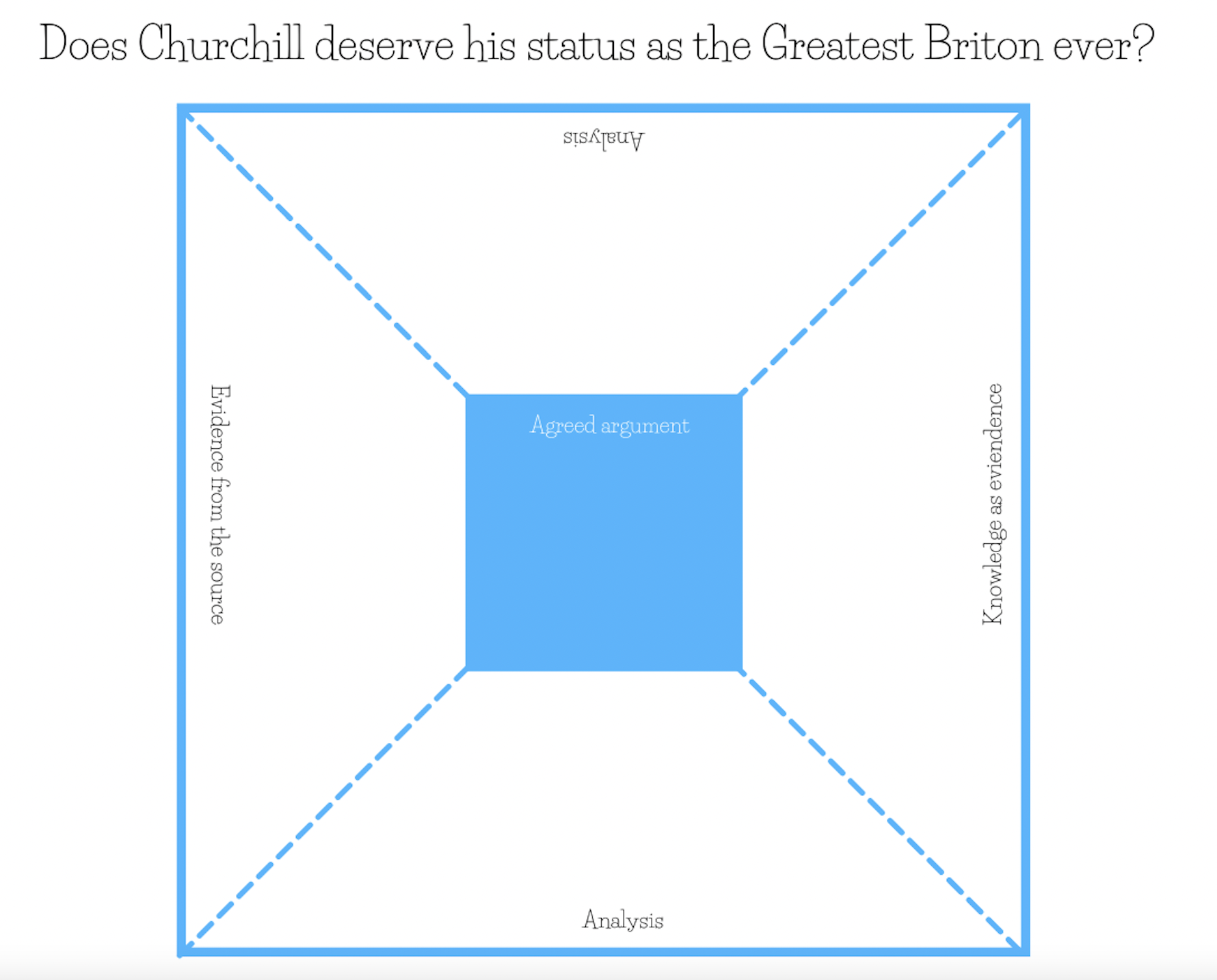

YOU COULD TRY THIS ACTIVITY TO PROMOTE COLLABORATION AND ORACY IN THE CLASSROOM. ASK STUDENTS TO COMPLETE THE ROTATING SQUARE, INDEPENDENTLY, IN 10 MINUTES. THEN IN PAIRS, STUDENTS CAN ROTATE SOMEONE ELSE’S SQUARE. READ THE ARGUMENT IN THE MIDDLE OF THE SQUARE AND PEER ASSESS THE KNOWLEDGE AND ANALYSIS FOR 5 MINUTES AND ROTATE AND ASSESS THE KNOWLEDGE AND ANALYSIS FOR THE NEXT 5 MINUTES. THE FEEDBACK THAT SHOULD BE INCLUDED IS WHAT WAS GOOD ABOUT THEIR WORK AND GIVE ONE THING THEY NEED TO WORK ON. BUT WHAT IS NICE ABOUT THIS ACTIVITY IS THAT STUDENTS RECEIVE FEEDBACK FROM TWO STUDENTS INSTEAD OF ONE.

To begin with, you may want to provide students with a writing frame to scaffold their ideas and structure their arguments, such as Point – Evidence – Explain – Link. The more you engage in debates, the less formulaic student response will be as they learn how to deliver persuasive arguments using well-developed evidence and analysis.

Sarah Gillen is the Programme Manager for Parallel Histories and previously a history teacher for 10 years.