What young people in Northern Ireland can teach the rest of us

It’s been fascinating working with school students in Northern Ireland over the last few years on the topic of the history of the conflict between Israel and Palestine. And not just fascinating but also heartening. It seems to me that these young people who have grown up in a post-conflict society (it’s now over 25 years since the Good Friday Agreement was signed) have something valuable to teach the rest of us about how to approach the history of a conflict when it has reached boiling point – as it has it has in the past couple of months.

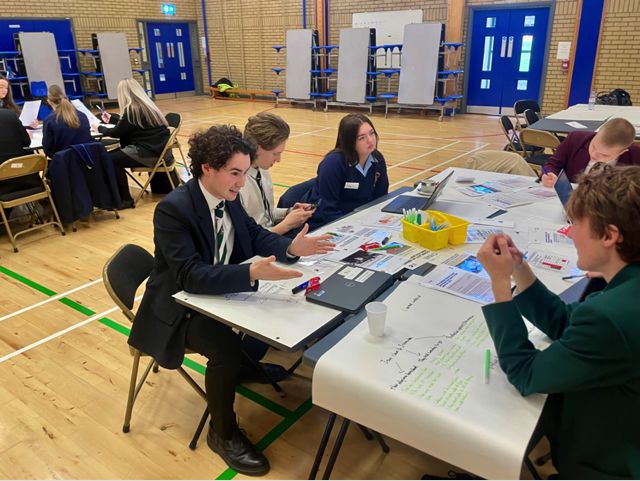

There are two positive behaviours which I’ve witnessed among students in Northern Ireland in our debating workshops – and my observations apply equally to both sides of the community. The first of these behaviours is that young people in Northern Ireland show a sensitivity about the use of language, which is far more developed than one would expect to find among students of the same age in a school in England or Wales. Northern Irish students, understand that words matter, and that the simple use of one word to describe a place or an event can alienate a listener. For example, anyone brought up knowing that if you call a town Derry, it signifies that you are Catholic and if you call it Londonderry, it signifies you are Protestant, will easily understand that it really matters whether in English you describe the West Bank as the OPT, which stands for Occupied Palestinian Territories, or Judea and Samaria. The first name shows support for Palestine, and the second term shows support for Israel. Northern Irish students are also attuned to the wrangle about who is allowed to apply the term terrorist to whom.

The second of the positive behaviours I have witnessed is that when these young people sit down at the table with their peer group from a different community, they come with an understanding that the conversation will go nowhere unless each side acknowledges the other side’s viewpoint. This applies both to specific issues and more broadly to acknowledging the other side’s historic narratives and cultural traditions. This doesn’t mean that each side agrees with each other – far from it – but it does mean that there is an acceptance that there are understandable differences of opinion. I think this comes from growing up in a post-conflict society. Both Protestants and Catholics recognise that they share a piece of land, and they need to work out how to share it peacefully.

I think this acceptance of the need to accommodate the other community is one of the few positive outcomes of the Troubles; after 30 years of sectarian conflict, it became clear that violence was leading to a dead end for both communities. So, watching Northern Irish school students discussing the rights and wrongs of the Israel, Hamas war is for me an encouraging and heartening experience which makes me optimistic about the future. They manage to tackle highly emotive and contentious questions with patience, consideration, and good humour. This contrasts sharply with the often aggressive and abusive discourse prevalent in online forums.

And this optimism is supported by several years of opinion polling, which shows that young people in Northern Ireland are becoming less sectarian in terms of how they identify. For example, they are less likely now than in the past to describe themselves as either Roman Catholic or Protestant, and more likely to describe themselves as non-religious. This doesn’t necessarily mean they don’t go to church anymore (although it might do) but it does mean they don’t want to identify in terms of their religion. In addition to this, there is a change in the way young people from both communities use the terms British Irish and Northern Irish. In the past, there was a clear distinction in that Roman Catholics identified as Irish, and Protestants identified as British. But those distinctions are gradually breaking down and there are more people from both communities who identify as Northern Irish – a shared identity that includes Protestants, Catholics, and those with no religious affiliation.

In the years after the Good Friday Agreement British and Irish politicians presented the progress made towards peace in Northern Ireland as a model for the Middle East.

Sadly, it’s hard to see the relevance of that model today. While in Northern Ireland young people are less sectarian than their elders, in Israel, the opposite is true. Polls show that on average 33% of Israeli Jews are in favour a two-state solution to the conflict but that drops to only 20 percent of Israeli Jews aged 18-34. This compares with 47% of Israeli Jews over 55 who support it. Young Israelis are therefore more likely to vote for right wing parties who are against any peace deal which swaps land for peace. And while polling data on the attitudes of young Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank is harder to come by, anecdotal evidence from journalists suggests that support for Hamas among the young has grown since October 7th 2023.

This makes the ‘Two State Solution’ favoured by the USA, Europe, the Arab League and the UN, increasingly harder to achieve.

However, in Northern Ireland, based on this polling and my own observations of young people, I think the picture is much rosier. Maybe we will need to wait for a new generation of political leaders, but it looks increasingly likely that Catholics and Protestants will accommodate each other and find a compromise agreement as to the constitutional arrangements.

Michael Davies is the Editor of Parallel Histories and a former history teacher. Parallel Histories runs debating workshops bringing together students from schools across Northern Ireland to discuss different perspectives on their shared history.