The Status Quo: Competing claims to religious sites in Jerusalem

“I shall never concede any road improvements to these crazy Christians as they would then transform Jerusalem into a Christian madhouse.” Faud Pasha, the Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire, 1865

Whatever the shape of the ceasefire that eventually emerges between Israel and Hamas, it will almost certainly have done nothing to defuse one of the prime causes of the conflict: the competing claims to Al-Aqsa/the Temple Mount. 81% of Palestinians recently polled said that the 7th October Hamas-led attack on Israel was, among other factors, “a response to settler attacks on Al-Aqsa Mosque”- one of the holiest sites in Islam sitting in Jerusalem on top of the most holy site in Judaism.

How do you decide between competing claims to a religious site? In the 19th century, the Ottoman government tried to answer this question by saying they were maintaining “the status quo”. It was a cop-out. It didn’t prevent Faud Pasha’s fears coming true: the European Christian powers transformed the landscape of Jerusalem through taking sides in disputes between Christian denominations. The Ottoman Empire had ruled Jerusalem since 1517. In a matter of decades, the religious politics of Jerusalem destabilised that power.

Yet governments today continue to rely on maintaining “the status quo”. The history of this concept- and of the arrival of the European Christian powers in Jerusalem in the 19th century which will be covered in this blog series- shows students how the daily life of worshippers and power politics don’t stand still. This history may also help us understand why competing claims to religious sites continue to cause conflict today.

This sketch is perhaps the most famous illustration of the idea of maintaining the status quo. The ladder below the upper right window of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (considered to be the site of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection in Jerusalem) has apparently not moved since at least 1728. Its purpose and origin are long forgotten. It is no longer used. Yet no one has dared moved it. Rather than risking angering the other Christian denominations by changing something in the Church, everyone leaves the ladder standing.

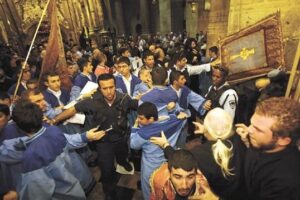

The ladder may seem absurd but disrupting the status quo at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre risks violence. 11 people were hospitalised in 2002. The Egyptian Coptic Christians position a monk siting on a chair on the roof of the Church to assert their right to the roof. On a hot day, a monk moved the chair into the shade. Ethiopian Orthodox priests saw this as hostile. The result was flying iron-bars and fists.

It is easy to see why successive ruling powers have preferred to keep things the same. Henry Luke, the British Chief Secretary of Palestine in 1929, described governments dealing with the Church as “the delicate duty of applying one of the most fluid and imprecise codes in the world”. Why try to carry out such a duty when you can just say that everything must stay the same? In 1922, the Mandate for Palestine obliged Britain to preserve the existing rights to “the Holy Places”. Israel affirmed its commitment to maintaining the status quo at the Church in its 1993 agreement with the Vatican.

However, the idea is not just the result of quarrelling priests. Faud Pasha was concerned about Jerusalem becoming a “Christian madhouse” because the European powers had arrived in Jerusalem from the mid-19th century. In 1808, they took little interest in the rebuilding of one of the most holy Christian Churches. A monk had fallen asleep. A stove set alight, and the Tomb of Jesus in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre was destroyed. Jerusalem did not have the strategic or religious resonances for Britain, France and Austria to take their eyes off the Napoleonic wars. Yet, by 1853, control of the Church had become a cause of a major international war in the Crimea War. Nicholas I of Russia was provoked by Napoleon III’s lobbying for the Catholic orders to have more control of the Church.

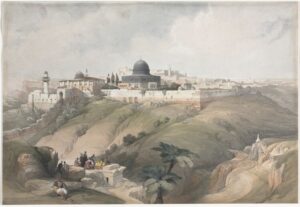

The European powers arrived with a religiously inspired mission to transform Jerusalem. The state of Jerusalem had surprised those Europeans who arrived in Jerusalem in the early 19th century. One English traveller reported: “The behaviour of the pilgrims was riotous in the extreme. At one point, they made a racecourse around the Sepulchre and some, almost in a state of nudity, danced about with frantic gestures, yelling and screaming as if possessed”. Artists’ romantic depictions of Jerusalem had shaped the arriving Europeans’ imagination. In response, they set to with building grand religious buildings. The French were explicit in describing this imposition on the Jerusalem landscape as a “mission civilisatrice”. However, behind all of the European powers’ projects was a desire to transform Jerusalem in accordance with their religious ideals- “Jerusalem the golden, with milk and honey blest, beneath thy contemplation sink heart and voice oppressed.”

However, the European powers’ concerns extended beyond who prayed at what time on Easter Saturday. The ability to influence the Ottoman Empire had come to matter in their power politics. Russia had designs on Istanbul. Britain wanted to project the trade routes to India through the Suez Canal. Germany would later in the 19th century seek to extend its power into the Ottoman Empire through securing the right to build a railway from Berlin to Baghdad. All sought to impose themselves on the Jerusalem landscape through the grand building projects. Through this patronage of Christian denominations, the European powers sought to establish power centres in Jerusalem and influence in the Ottoman Empire. It is no surprise that Faud Pasha did not want to “concede any road improvements”.

Imperial politics and religious claims in Jerusalem became intertwined. The Ottoman administration needed a solution to prevent the emotions about use of the Church leading to the European powers undermining its control of the city. The solution the administration settled on was to decree in 1852 and 1853 that no change can be made to the state of affairs at the Church (and other Christian religious sites in Jerusalem and Bethlehem). In so doing, it revived an idea it had used a hundred years earlier to resolve competing claims between the Orthodox and Catholic religious orders for control of the Church. In 1757, the Ottoman Sultan is supposed to have decreed that the balance of control of the Church of the Holy was to stay the same. The decrees in 1852 and 1853 enshrined the idea in legal form.

The idea of the status quo was enacted in Ottoman law. It was recognised in international law in the Treaty of Berlin in 1878. Yet it didn’t stop the transformation of Jerusalem. By 1900, the landscape of Jerusalem was unrecognisable from the early 19th century. The fabric of daily life changed with it. This blog series will look at these changes through the actions of Britain, France, Russia and Germany, and of local and immigrant Jews, the Ottoman administration and the local Arabs. It will trace how the arrival of different sources of power and the competition for use of religious spaces created a new Jerusalem on the eve of World War One. It will illustrate how competition for religious sites can unravel governments’ plans and agreements.