The French in Jerusalem

There are surprisingly few French government buildings in Jerusalem. France spent a lot of diplomatic, and indeed military, capital over Jerusalem in the nineteenth century. Yet the government did not bother to establish a physical presence in the city. French pilgrims and religious orders financed the construction of plenty of buildings in the nineteenth century but there is no French equivalent of the Russian Compound, or the German Church of the Redeemer. After Napoleon’s failed invasion of the ‘holy land’ in 1799, it would have been understandable if the French government tried not to provoke the Ottoman Empire. Nevertheless France supported Mehmet Ali in his rebellion against the Ottomans in the 1830s: a rebellion that resulted in Ali using his base in Egypt to conquer much of Greater Syria (modern day Israel, the Palestinian Territories, Lebanon and Syria) from the Ottomans. And it was not idle support of some foreign rebellion, with all to gain and nothing to lose, since the British and the Russians intervened to defeat Ali, on behalf of the Ottomans. Emperor Napoleon III decided he needed some Catholic prestige, after overthrowing the Second French Republic in 1851, and so was prepared to escalate a dispute with the Russians over control of the Church of Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, into the Crimean War. Even then, few government buildings were established in Jerusalem. France was the first nation to be granted special status in Jerusalem. The first of the Capitulations was signed in 1525, which granted the right to protect its traders and priests. Still there were few official buildings in Jerusalem to show for that long diplomatic influence over the city.

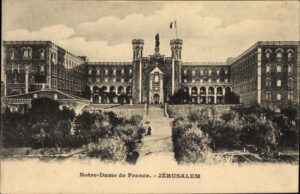

The most striking French building, the Notre Dame de France, is now indistinguishable from other hotels, on the inside. Outside it is still a resplendent statement of French Catholicism. The chapel has the airless atmosphere of other churches used more by tourists than worshippers but the statue of Mary stands, gleaming in white stone, surrounded by two towers, on the highest point overlooking the Old City. The statue of Mary was the first public statue of the mother of Jesus, when it was added to the Notre Dame in 1904. The rest of the building was finished by 1890 in a strictly symmetrical, neoclassical style, supplemented by Oriental style battlements on the roof. The flaunting of French Catholicism through a neoclassical style is also evident in the Ratisbonne Monastery that began construction in 1874. Marie-Alphonse Ratisbonne also financed the Convent of the Sisters of Zion on the Via Dolorsa in the Old City. The Convent shows French Catholicism embracing the Christian traditions of Jerusalem through its imitation of a Byzantine basilica. The Church of St Anne (rebuilt after being granted to Emperor Napoleon III in 1856) and the École biblique et archéologique (founded in 1890) also display the features of a basilica- a central aisle marked by two rows of columns and flanked by two side aisles, a rectangular shape with a semicircular apse at the altar end, topped by a dome, a liberal sprinkling of mosaics. Edouard Blondel, a French businessman, complained that a “curtain of domes and minarets hid the cupola of the Holy Sepulchre.” The French could not remove that curtain but their buildings exhibit a desire to “christianise” the landscape of Jerusalem.

THE DOME OF THE CONVENT OF THE SISTERS OF ZION

Blondel was disappointed that the reality did not match what he imagined. The French came to Jerusalem in the 19th century because they wanted, to quote one French pilgrim, ‘a memory and an emotion. This memory, the very stones render it to your soul; this emotion, everything contributes to its birth: the number and the layout of the sanctuaries, the mysterious twilight of the vaults, the byzantine decoration.’ This memory and this emotion were tied to the landscape of the city and the expectation of that landscape was provided by Chateaubriand’s Itinéraire de Paris à Jérusalem, published in 1811. An industry of books about travelling to the ‘holy land’ followed the Itinéraire but Chateaubriand was the instigator of the image in French minds of ‘Everywhere a land teeming with miracles: the burning sun, the towering eagle, the barren fig-trees, all the poetry, all the images of Scripture are there… God himself has spoken here.’ It is a romantic image of a changeless and backward land, and it would not do if the inhabitants of that land spoiled the memory and the emotion by building domes and minarets.

Impressive neoclassical buildings and basilicas do not match exactly onto this image of Jerusalem though. They are not changeless, romantic ruins. 1000 rich French Catholics were forced to sleep in tents in 1882 because of a lack of accommodation in the city. They financed the building of the Notre Dame. The majority of French pilgrims were rich, either aristocrats or the upper middle classes, in contrast to the peasants that largely made up the Russian pilgrims. The first organised pilgrim group left Marseille in 1853 but it was after 1870 that the movement really got going. An embarrassing defeat in a war with Germany had created a crisis of confidence which Catholicism, and in particular pilgrimage, sought to fill. These pilgrims needed somewhere to stay. There may have been no room in the inn for Jesus but French pilgrims ensured there were luxury hotels for them.

So Jerusalem disappointed the French through differing from their imaginations and through its lack of accommodation. Its people also did not match the standards of the French. Chateaubriand may have celebrated the local inhabitants having ‘the same manners which they have retained ever since the days of Hagar and Ishmael.’ Gustave Flaubert’s reaction to Jerusalem- ‘charnelhouse surrounded by walls, the old religions rotting in the sun’- was more in keeping with his compatriots’ thoughts about the locals, if the anti-religious sentiment is ignored. The “Mission Civilisatrice’ took on a new edge in Jerusalem. The Ratisbonne Monastery was originally intended to be a school. The many other French schools and missionary buildings were part of a greater cause than just teaching the locals French. This was the peaceful crusade. France, as the self-proclaimed heir to the Crusaders, returned to the city with books instead of swords. Like the original Crusaders, convinced of the righteousness of Catholicism, their target was as much Eastern Christians as Muslims. The decaying, romantic city was a beautiful image for faith but this city had once flourished under the French and it would again. Or at least that was the idea.

Politics played a role too in the forging of this crusade and the building of statements of French Catholicism. The location of the Notre Dame was chosen because it was between the Old City and the Russian Compound and thus blocked the Russians’ view and direct access to the city. Governments though were less adept at the game. The first French consul, in the 1840s, had tried flying the French flag. It was torn down, paraded through the streets and replaced on the flagpole by a slipper. Brazen displays of governmental influence did not go down too well with the locals. The European governments did have some influence because they could legally protect individuals. Yet as Gérard de Nerval noted, the result was more chaotic than colonial power-grabbing: ‘there isn’t a thief, a murderer or a delinquent who does not succeed in putting himself under the protection of some consulate or other. There are twenty police forces which cancel one another out; yet it is the pasha who is supposed to be responsible.’ It was the religious orders and pilgrims, with their dreams of a New Jerusalem civilised by the French, that left a permanent mark on the city.