Diversifying the Teaching of the First World War: The Battle of Broken Hill

The massive reaction we got to Elena Stevens’ blog about diversifying the teaching of World War One is proof that teachers are looking for stories about this global war which do not come from the Western Front. Her story of the two brothers is fascinating and there are a myriad of others.

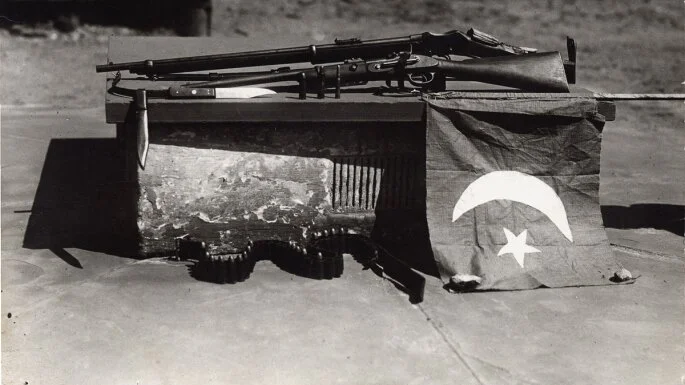

One such story is how the Ottoman Sultan’s call for jihad against Britain, France and Russia led to six deaths in the Australian outback on 1 January 1915. Badsha Mehmed Gül and Molla Abdullah had come to Australia from India as camel drivers. By 1915, Gül sold ice-creams while Abdullah was a butcher. Inspired by the Sultan Mehmed V’s call for Muslims worldwide to “throw yourselves against the enemy as lions”, they hid weapons in Gül’s ice-cream cart, positioned themselves on a hill and opened fire on a passing train. The passengers were on their way to a picnic. They only realised the shots were not part of the day’s entertainment when four dropped dead. The train pulled over. A posse assembled. Weapons were found. Gül and Abdullah were later that day killed hiding in a quartz mine.

Abdullah had been discontented for sometime. The local authorities had fined him repeatedly for slaughtering animals according to Islamic law, rather than according to local practices. It was Gül who convinced him to take up arms: “I rejoiced and gladly fell in with [Gül’s] plans and asked God that I might die an easy death for my faith”. Gül seems to have quickly accepted the Ottoman declaration on 14 November 1914 that: “the Muslim subjects of Russia, of France, and of England and all the countries that side with them in their land and sea attacks dealt against the Caliphate for the purpose of annihilating Islam, must…take part in the holy war against the respective governments.” Great power rivalry met local religious discontent at the Battle of Broken Hill.

Such a story helps us draw our gaze away from the Western Front. Here is an introduction to the idea that the belligerents on the Western Front were global empires. Events happened a long way from the Western Front because the countries fighting had colonised other parts of the world. The mobilising power of ideology is also there in Abdullah’s explanation. Interest, diversity, ideology: the usefulness of this story emerges from these ingredients.

Students may see in Abdullah’s explanation a comparison with calls for global jihad today but before they take that comparison too far its important to note the differences between then and now. It was not an armed group claiming control of parts of modern-day Syria and Iraq that issued the declaration of jihad but a major empire that had governed much of South-East Europe, the Middle East and North Africa for four centuries. The sovereign of 24,000,000 people had entered a war between European powers in order to protect his territory from some of those powers. In so doing, he called on the 100 million Muslims living under British rule, the 20 million under French rule and the 20 million under Russian control to abandon any political loyalties they felt and rise up in the name of their religious identity.

So Abdullah and Gül stood on an Australian hill with an ice-cream cart and shot four people because of a deal between the Ottomans and the Germans. The Ottoman Empire had mobilised its army in response Russian territorial aggression after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Members of the Ottoman elite decided to accept German money to keep the army mobilised and in return Sultan Mehmed V declared jihad against the German enemies of Britain, France and Russia.

The German empire was the dominant partner in this deal. The Ottoman Empire needed the money more than the German empire needed the declaration of jihad. The declaration still had its uses for the Germans. A German newspaper declared: “The enemy lost 40 killed and 70 injured. The total loss of Turks was two dead. The capture of Broken Hill leads the way to Canberra, the strongly fortified capital of Australia.” Here is a German newspaper seeking to reassure its readers about the direction of the war. Our histories of the war may predominantly focus on the Western Front but contemporaries were alive to the ‘world’ dimension of the war.

In spite of the power and weight behind the call for jihad, it was remarkably ineffective. It was only Abdullah and Gül stood on Broken Hill and there were few other incidents across the world.

Some even disobeyed the Sultan. The second highest authority in Islam after the Sultan proclaimed a revolt against the Sultan. Sharif Husayn, guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina, initiated the Arab Revolt on 10 June 1916. An Arab army under Husayn and his sons expelled the Ottoman army from the Hijaz (the region of Mecca and Medina) and went on to capture land as far north as Damascus. Approximately 5000 Arabs, growing to 30,000 or more as the army approached Damascus, joined the army. They followed Sharif Husayn who had accepted support from the government of the country against which Sultan Mehmed V had proclaimed holy war: Great Britain.

To draw a comparison between these individuals and Abdullah and Gül may seem ridiculous. The aspirations of the Arab Revolt were more political and nationalistic than religious. The differences in nationality, form of religion, lifestyle are almost too much to make a comparison between Abdullah and Gül and the individuals who participated in the Arab Revolt. Yet the Sultan Mehmed V’s declaration of jihad was a cause of their different actions during World War One. For Abdullah and Gül, it was the motivation to rebel against those who governed them. For Sharif Husayn, the declaration presented the opportunity to realise his aspiration for power and Arab aspirations for independence.

Here is a World War One in which the European powers create the scenery but are not in the spotlight on the stage. The Ottoman Empire called on Muslims to fight in World War One as part of its efforts to protect its land. Muslims responded or did not respond according to their local circumstances and beliefs.

Like the story which Elena told about Mir Dast and Mir Mast, this story adds a variety and richness to our understanding of World War One. The focus of exam boards and therefore textbooks on the Western Front, reinforced by the focus of the centenary commemorations which took place 2014-2018, has given today’s students an imbalanced picture of what after all has been called the First World War.

Joshua Hillis is Deputy Editor of Parallel Histories

Quotes from E.Rogan, The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East (2015)