Using the Parallel Histories approach to promote debating at A Level

At our school, all Sixth Form students are allocated a double lesson each fortnight for ‘Enrichment’ activities – and last year I realised that this provided an ideal opportunity to engage some of the students in debate. I was keen to use the Parallel Histories approach, and so planned the first couple of sessions around the debate topics ‘Which group had the strongest claim to the land between the Mediterranean and Jordan?’ and ‘Should the British Government be praised or blamed for the Balfour Declaration?’ Later, I switched focus to the Conflict over the Union, planning debates including ‘Has the Union been good or bad for Scotland?’ and ‘Does Brexit justify Scottish independence?’

Students are given a selection of Enrichment activities to choose from, and I presumed that most of the places in my sessions would be filled by year 12 and 13 History students – however this wasn’t the case at all, and as I looked through the sign-up lists I realised that I didn’t know many of the students who had chosen to attend the sessions, many not having taken History at either GCSE or A Level. This worried me: how much time would I need to spend introducing these students to the historical context? Would students have an understanding of the ways in which evidence is used to support arguments, or would I need to deconstruct this for them? How could I ensure that the debates were properly grounded in ‘history’?

My concerns proved completely unfounded. The Parallel Histories approach proved to be the perfect vehicle for the discussion of topics that are relevant and engaging for students who are studying History, as well as those who are not.

In adopting the Parallel Histories approach for these sessions, four main benefits really stood out:

1: The Parallel Histories videos help to ‘set the scene’.

I didn’t want the Enrichment sessions to feel like extra lessons, so I was keen to avoid overloading students with too much information. Using the Parallel Histories videos on the Israel/Palestine conflict helped to provide the necessary context, but the videos don’t give unnecessary detail – and watching them didn’t take up too much time. Of course, many of the students drew on their own knowledge of the conflict, or carried out additional research to substantiate points that they wanted to make, but additional knowledge was not a prerequisite to the formation of effective arguments.

2: The sources provided by Parallel Histories can be adopted and adapted according to the time available, and the types of students involved.

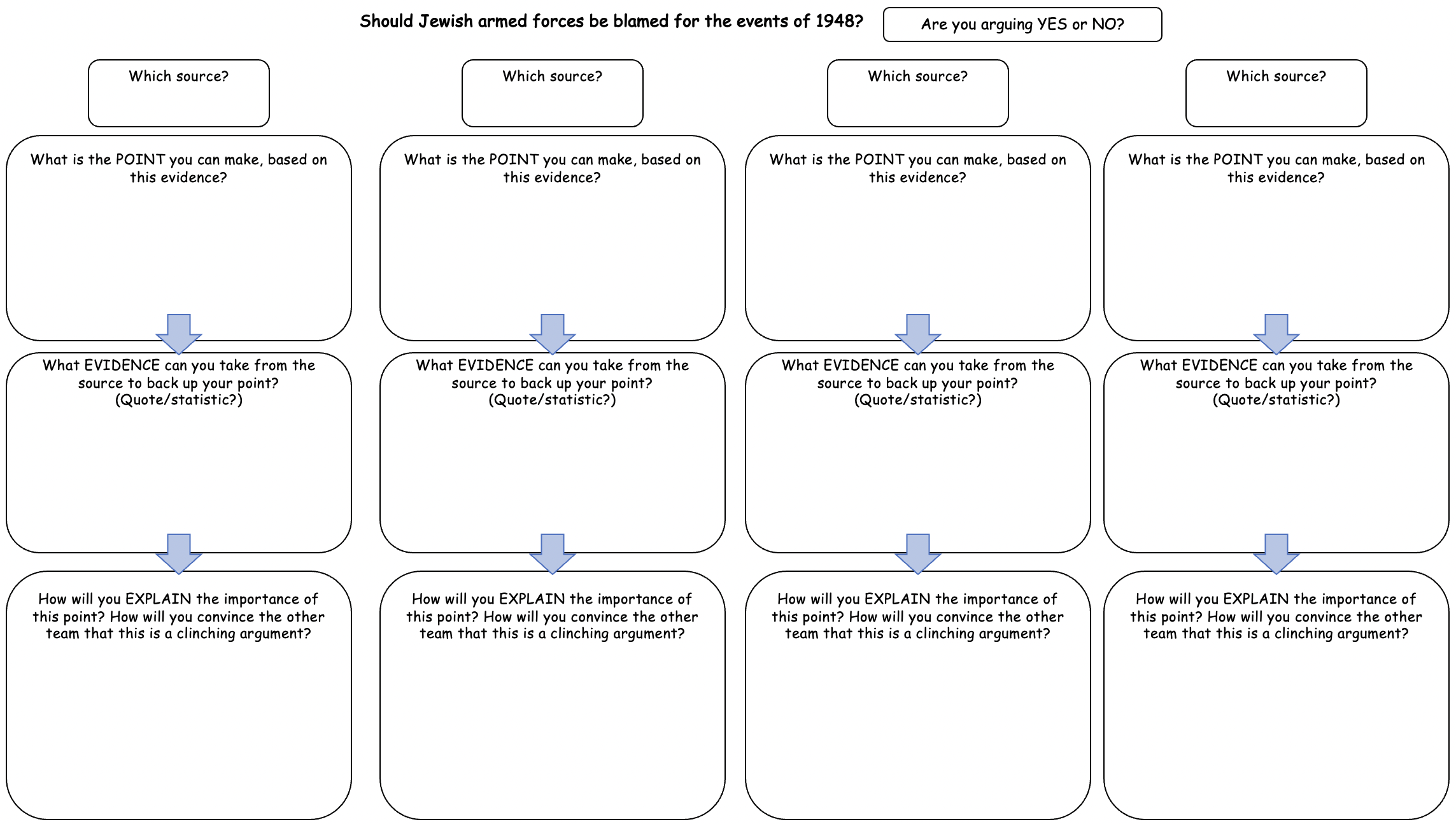

With only a limited amount of time to prepare for their debates, I chose four sources for each ‘team’, and encouraged them to use these to shape their arguments. Whilst I am keen for my A Level historians to unpick the provenance of any sources they encounter, I think that this aspect of source analysis does need the correct framing (otherwise, students’ stock response tends to be the relatively unhelpful ‘The source is biased’!) – so I encouraged students taking part in the debates to focus on the content of the sources first and foremost. I created grids like the one below to help students organise their ideas.

3: Focused on topics with (at least) two genuine interpretations or ‘sides’, the debates proved engaging and accessible for all students.

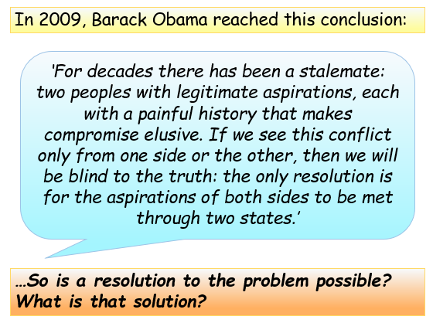

The debate topics were motivating for those students who did have a genuine knowledge and prior interest in the topics, as well as those who did not – and both of these groups of students were able to formulate relevant and well-reasoned arguments. The topics have a clear relevance to contemporary global events, and I ensured that we finished off our sessions with discussion of modern/recent developments (the slides below show some of the ways I tried to do this, in relation to the Conflict over the Union, and conflict in Israel/Palestine).

4: Students were highly motivated by the prospect of debate – particularly when they were pitted against students from other schools.

Although the debates suited our Enrichment schedule well (with the double lesson being divided into preparation time, time for the debate and a final reflection on the debates that had taken place), those students who were also taking part in Digital Debates were particularly motivated to use the Enrichment time to formulate effective arguments, and to ‘try out’ their debating skills ahead of the online debates.

Students really enjoyed debating against students from other schools. I think that competitive spirit helps to explain the initial attraction of the debates, but once students were immersed in the debates they became caught up in the arguments themselves, and were keen to convey their own points in the most convincing and eloquent way possible. I enjoyed listening in to the students as they waited in the ‘breakout room’ for their second debate to begin: they spent the time honing their points and practicing their speeches, helping their teammates come up with rebukes for arguments that they expected their opponents to make. It was great to see their passion and enthusiasm!

This is one student’s reflection on her involvement in the Digital Debates:

“I think debating is an important skill for all students, but it becomes especially important at A-level when many subjects, such as History and RE, need you to formulate your own judgements and opinions. This structure is quite different to GCSE, so debating helps you to build up the skills of forming and supporting arguments. I also really enjoyed it because I had the opportunity to explore different topics that I had not researched before. It definitely highlighted the importance of using contextual knowledge precisely and effectively, and how to respond to contrasting arguments in a way that still supports your point.

As someone applying for a Law degree at university, the skills involved in debating are highly transferrable and therefore boosted my personal statement – as although being involved in debating is not directly linked to the study of Law itself, it is still evidence that I am developing the skills that I will need as a Law student in the future.” (Sofia, year 13)

I’m really looking forward to seeing more of our students take part in debating opportunities this year, as well as using the Parallel Histories approach to develop students’ discussion and debating skills at KS3, KS4 and KS5.

Elena Stevens teaches History at St Philip Howard School in West Sussex. She has a PhD in History from the University of Southampton and is an advocate of teaching history through unconventional perspectives.