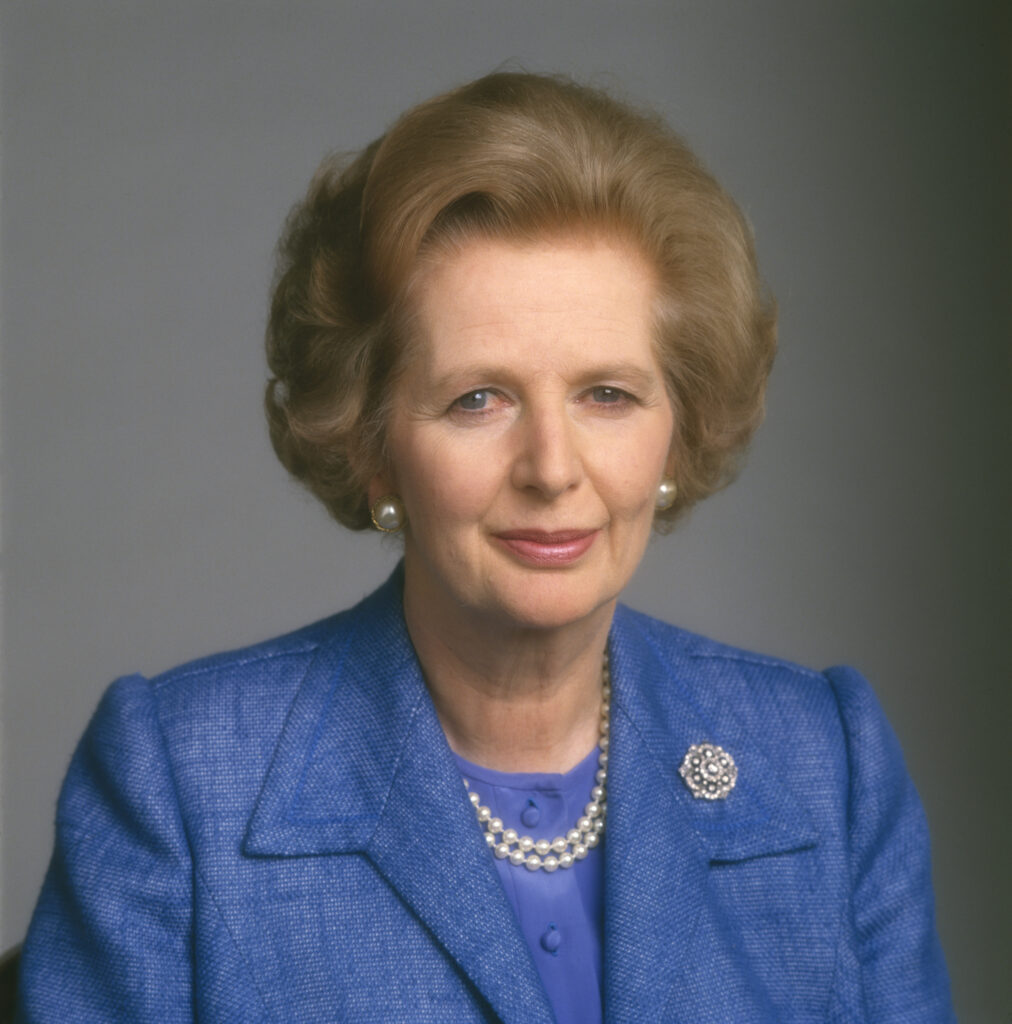

Where there is discord, will invoking Thatcher’s memory bring harmony?

Following the bitter and drawn-out removal of Boris Johnson Prime Minister earlier this year, the Conservative Party found itself tussling over who the next leader would be. This led to the familiar sound of Thatcher and Thatcherism being invoked as the ultimate Conservative authority in all areas of policy and in the case of Liz Truss, fashion! Both Prime Minister Sunak and ex-Prime Minister Truss were keen to invoke her memory, despite both being children when she left office. They clearly believed that reminding people of Thatcher was a sure-fire way of uniting and winning over the party membership. However, Truss and Sunak’s appeals to Thatcher as a unifying figure stand in direct opposition to her record in government (1979-1990), which suggests that far from uniting the country or her party, she thrived on competition and dissention.

Famously beginning her premiership with the words ‘where there is discord may we bring harmony…’[1]Thatcher was a conviction politician who was steadfast in her refusal to deviate from her plan to shake up the establishment and the country more generally. For eleven years she governed, as her ‘Iron Lady’ nickname suggests, with an iron fist and divided the nation both domestically and internationally. The divisions that such a way of governing brought are still present today, with people either loving or loathing her and very few being indifferent. The impact of Thatcher’s governments has reverberated throughout the United Kingdom and around the world, for good and for bad. She created a deep routed ideology in society that will continue to have implications for generations to come, notably the more individualistic society that Britain has become as opposed to the collective community of days gone by.

When looking back on her use of St Francis’s prayer she promised truth, faith and hope from her government. Of these promises, truth and faith stand out. In terms of truth, Edgar Wilson claimed that ‘Disingenuousness became the normal mode of communication of a government infamous for being economical with the truth.’[2] As far as faith is concerned however, her resignation was the moment she lost faith, not in her country or the electorate, but in herself. In that moment, the composure and control she had appeared to have for eleven years, dissipated.

Margaret Thatcher was renowned for being critical of those around her, but here, her self-analysis is complimentary of her own characteristics, critical of the Establishment and proud that she offended people, believing it was what the country needed. She never set out to be loved by everyone in Britain but sought to ‘defeat the establishment’s defeatism’ and pull the nation back from the economic hole it found itself in.[3] She went about this with the force and conviction not seen in Britain since Winston Churchill’s wartime government; ‘In a House of Commons dominated by men, she demonstrated an energy, thoroughness and grasp of her brief that few of her contemporaries could match.’[4] Thatcher herself claimed that: ‘I was not only a woman, but “that” woman. Someone not just of another sex, but of a different class, a person with an alarming conviction that the values and virtues of middle England should be brought to bear on the problems which the establishment consensus had created. I offended on many counts’[5] Thatcher wanted to give the people of Britain hope and pride in their country once again In many respects, she did exactly that, however the transformation of Britain from a manufacturing based economy to a services based economy destroyed the lives of many communities and divided a nation.

When it came to the premiership of Thatcher, you always knew what you were getting, when she declared a policy was going to be implemented, very little could change her mind. Initially, the economic situation within the UK became increasingly worse in the first few years, however by 1983, Thatcher was electorally strong enabling her to become more radical due to an increase in power within Parliament. Thanks to her victory in the Falklands and the Right to Buy scheme (Housing Act, 1980), broadly speaking, people appreciated consistency in doing what she set out to do. This is ultimately reflected in her 1983 victory in which the Conservatives won 397 seats giving them a majority of 144 in the Commons.[6] If anything, one of the problems some colleagues had was that she was not being radical enough regarding the economy. Strengthening a relationship with America under the presidency of Reagan and initially putting Britain in a better position within the European Community (EC), Thatcher worked tirelessly to make Britain the best country it could be in the only way she knew how.

There were three big policy concerns that caused significant rifts within the Conservative Party. These consist of the Westland Affair (1986), Europe (notably 1988 and 1989) and the Poll Tax (1989/1990). Eric Evans alleges that the Westland Affair marked the beginning of Thatcher’s downfall as well as providing an early indication of the divisions in the party over Europe. It was the point at which Michael Heseltine resigned from cabinet and the moment at which the vulnerable side of the Iron Lady was clear to see despite the protection provided by Bernard Ingham and Charles Powell.

While Britain has always had an awkward relationship with the EC, the increased efforts of the Community to defend against the Cold War and bring about further political and economic integration, was a key catalyst in Margaret Thatcher’s removal from office. As a result of Thatcher’s hostility to the EC against public approval, her personal ratings began to dip to the point that by 1989 and 1990, more people disapproved than approved of her handling of the EC. Whilst, she saw a high point in approval following the Bruges speech, she was not winning the British people over to her confrontational approach.

It was not until the Party Conference of 1989 that the issues with the Poll Tax became intrinsically linked to the leadership question, however, for many ministers it was an issue that could and should have been dealt with in previous years. For Lawson, the problem was undoubtedly Thatcher; despite all the trouble it had caused for the government when introduced in Scotland (1989) Thatcher had ‘become too committed […]to contemplate drawing back.’ The miscalculation and backlash against the Poll-Tax highlights the political singlemindedness that had been a defining characteristic of her tenure as Prime Minister, and which significantly contributed to her being forced from power by her own colleagues.

Despite all these factors, Thatcher was a ‘woman who succeeded against all the odds, in a man’s world.’ Whilst she did not manage to maintain relationships with her colleagues in government, in the way that she achieved with international statesmen like Reagan, she successfully won over the electorate on three separate occasions, irrespective of the damning economic situation and her aggressive handling of European policy. She was the first woman to achieve the British Prime Ministership and consequently normalised female success for women globally. She continues to influence policy over thirty years later. Her increasingly aggressive attitude towards the men in her cabinet over policies she wished to pursue continuously worked against her. Gradually, ministers became too weary with the fallouts. As reflected on by Lawson this was an issue that did not stay within government but had a significant impact on her electorally, he concluded that ‘in the early years the votes gained by her strong personality clearly outweighed the voted lost by it. In her third term the balance began to switch.’

Does all this mean that Sunak and Truss were wrong to try and use Thatcher’s memory to unite the Conservative party? Not necessarily, after all the party has changed greatly since Thatcher’s heyday in the 1970s. However, Thatcher’s actions in government do suggest that her role within the Conservative party, let alone the country, was far more contested than Truss and Sunak portrayed it. Thatcher’s reign as Prime Minister demonstrates that keeping a party united requires far more than superficial invocations of past leaders. It heavily relies on the popularity of policy amongst the public and the ability of a Prime Minister to navigate the social niceties required of their premiership. Whether Sunak is aware of this and possess the skills necessary to hold the party together for as long as Thatcher did remains to be seen.

Hannah Coltman teaches History at The Polesworth School in Staffordshire

[1] Margaret Thatcher, ‘Remarks on becoming Prime Minister (St Francis’s prayer)’, Margaret Thatcher Foundation, (4 May 1979) https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/104078 [accessed on 16 July 2020].

[2] Edgar Wilson, A Very British Miracle The Failure of Thatcherism (Pluto Press, 1992), p. 194.

[3] Bernard Ingham, The Slow Downfall of Margaret Thatcher The Diaries of Bernard Ingham (Biteback Publishing Ltd, 2019), p. 340.

[4] Virginia Bottomlet, ‘Margaret Thatcher’, in Iain Dale and Jacqui Smith (eds.) The Honourable Ladies Profiles of Women MPs 1918-1996 (Biteback Publishing, 2018), p. 247.

[5] Margaret Thatcher, The Downing Street Years (Harper Collins, 1993), p. 130.

[6] ‘1983 General election results summary’, UK Political Info,http://www.ukpolitical.info/1983.htm#:~:text=Table%3A%201983%20general%20election%20results%20summary%20%20,%20%20%2B2%20%206%20more%20rows%20[accessed 24th July 2020].